This is the second of a two part post on the Oregon Treaty and its aftermath. Part 1 can be found here.

Earlier this week, we left our story of the Oregon Treaty on its peculiar instructions for the border between British and American controlled lands: following the 49th parallel to the Strait of Georgia, and then following the “middle of the channel” to reach the Strait of Juan de Fuca and then ultimately the Pacific Ocean. The maritime route of the boundary established in the treaty accomplished a top British objective of retaining control of the entirety of Vancouver Island. But in the waters between Vancouver Island and the mainland of American territory, confusion over the “middle of the channel” meant that the San Juan Islands would become a flash point in the U.S./British boundary disputes of the Pacific Northwest.

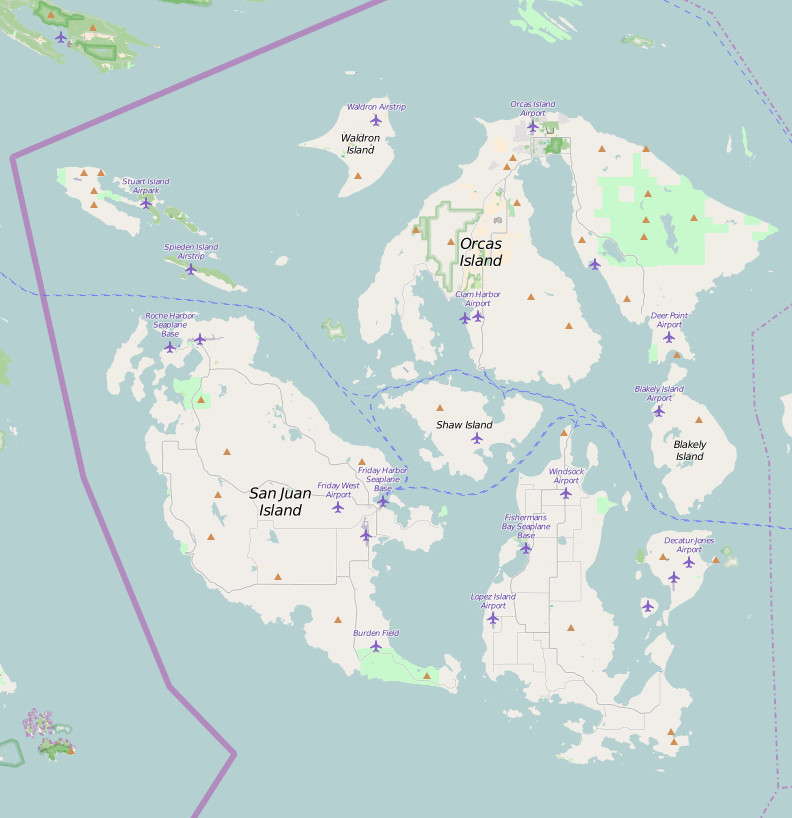

The San Juan Islands are an archipelago in the Salish Sea that is a part of the present day U.S. state of Washington. Within this archipelago is San Juan Island, the most populous island in the archipelago and the specific setting for the ratcheting up of regional tensions described later in our story. The modern geography of the San Juan Islands archipelago can be seen below, in this extract from OpenStreetMap.

After 1846, in interpreting the Oregon Treaty, Americans argued that the Haro Strait (also known as the Canal de Haro) to the west of the San Juan Islands was the true boundary, as it was geographically the widest and deepest channel in the region, and a natural border feature. The British, however, claimed that the true boundary suggested in the treaty was the Rosario Strait to the east of the San Juan Islands, thereby claiming the islands for Britain.

In negotiations to settle the boundary dispute in 1857, British commissioners presented an interesting piece of evidence to bolster Britain’s claims: an 1848 map of Oregon and Upper California drawn by American surveyor John C. Frémont that was commissioned by the United States Senate. The map aligns with Britain’s claim of the San Juan Islands, with the boundary passing to the east of the islands through the Rosario Strait. Below is a closer look at this controversial map detail.

Despite this cartographic evidence and the consideration of a compromise boundary line through the middle of the islands, negotiations collapsed without a resolution. The San Juan Islands remained in political limbo, as American settlers and employees of Britain’s Hudson’s Bay Company occupied the disputed territory. It would be another two years before an unusual event would force the issue of boundary reconciliation.

One night, on San Juan Island, American farmer Lyman Cutlar awoke to the familiar sounds of a pig foraging in his potato patch outside. The pig was an unwelcome repeat visitor to the garden, but this time, Cutlar had had enough. He took his rifle and shot the pig, killing it. The pig was owned by Englishman Charles Griffin, who operated the Hudson’s Bay Company’s nearby sheep ranch. Griffin confronted Cutlar to demand compensation for the dead pig. In a comical exchange between the two men (which has perhaps been embellished in retellings of the story), Cutlar argued that the pig was trespassing on his land and eating his potatoes, to which Griffin replied, “it is up to you to keep your potatoes out of my pig.”

Based on the notion that San Juan Island was British territory, Griffin contacted British authorities to have Cutlar arrested. In response, Cutlar and some of his fellow American settlers on the island petitioned the United States military for protection. What followed must have been a surreal experience for the sleepy San Juan Islands: three British warships, over 2,000 British troops, more than 400 American troops, and a multitude of cannons on both sides descended on the area in a massive show of military force. A tense standoff ensued, with British and American forces preparing for the possible outbreak of war.

When word of the escalating situation finally reached Washington, D.C. in September, President James Buchanan was horrified at the prospect of war breaking out over such circumstances. Buchanan sent General Winfield Scott to the San Juan Islands to calm the situation and through his efforts, British and American officials agreed to a reduction in military forces and established a joint military occupation of San Juan Island, with a British camp stationed in the north of the island and an American camp to the south. The “Pig War” had come to an end with no human casualties.

It wasn’t until 1872 that the boundary was finally settled. Great Britain and the United States agreed to have the issue decided through international arbitration, having Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany serve as an arbitrator in the dispute. The arbitration commission ultimately ruled in favor of the Haro Strait boundary line, which granted the United States control of the San Juan Islands and essentially finalizing the U.S.-Canada border in the Pacific Northwest that we know today.

With the modern boundary between the U.S. and Canada settled, there is a peculiar remnant of the 49th parallel border set out in the Oregon Treaty. Located at the tip of the Tsawwassen Peninsula, the town of Point Roberts, Washington is a land exclave of the United States, meaning that it is separated from the U.S. mainland and it can only be reached by land from the U.S. mainland by traveling through Canada. The stringent nature of the 49th parallel as a boundary line, with U.S. territory established for all areas south of this line, is responsible for this strange political geography. An early example of Point Roberts on a map with American status can be seen in “Map of Public Surveys in the Territory of Washington,” created by Joseph S. Wilson in 1865.

The story of the Oregon Treaty and its aftermath is a certainly wild one, from its tumultuous creation, to its bizarre implications for the San Juan Islands and Point Roberts, to the near-outbreak of war over the most unbelievable of circumstances. As is often the case in establishing international boundaries, separating the U.S. from present-day Canada wasn’t an easy process. But through a thankfully (almost) bloodless process, we have a border and a fascinating story to go with it.